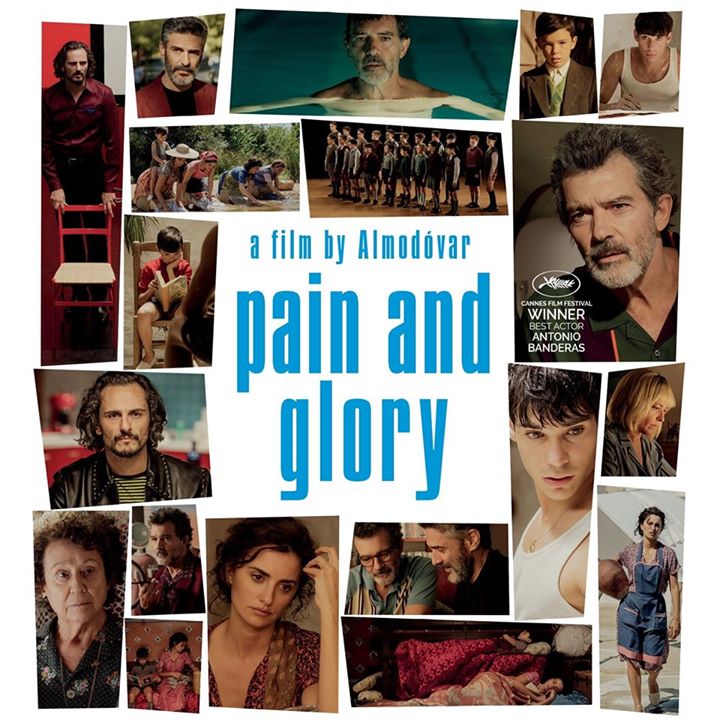

Pain and Glory

Pain and Glory (Dolor y Gloria)

Release Date: October 4, 2019

Runtime: 113 minutes

Rating: R

Studio: Sony Pictures Classics

Director: Pedro Almodóvar

Cast: Antonio Banderas; Penélope Cruz; Asier Etxeandia; Leonardo Sbaraglia; Nora Navas; Julieta Serrano; Asier Flores; Cecilia Roth; César Vicente

**Reviewed at the 57th New York Film Festival – September 29, 2019**

Pain and Glory, the newest from Spanish auteur Pedro Almodóvar, provides singular testimony to the universal emotional truths that connect us as people. It is one of the best films, from its remarkable central performance from Antonio Banderas to its subtle, yet powerful impact, films I have seen in a long time. Pain and Glory reaches its audience on a variety of emotional levels, from the evocation of a child’s curiosity, the torture of self-doubt and depression, the mourning of loss, the hope that comes with renewed energy….all of it.

Exhibiting an extraordinarily natural style and poise, Almodóvar muse Banderas plays Salvador Mallo, a not-so-veiled version of the director himself. After years of suffering from an assortment of chronic pains, Salvador, a once heralded film director, has retreated into a shell of himself and succumbed to a debilitating malaise of life. A local cinematheque, however, has expressed interest in screening Salvador’s most famous work and Salvador has reluctantly agreed to present the film alongside its star, Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia), a former star-cum-drug addict with whom Salvador has a very public and rocky history. This rekindling of their damaged relationship leads promptly to Salvador’s own drug addiction, only serving to deepen the darkness in which he has lived for so many years. Without much to occupy his time other than his chronic pain and his thoughts, Salvador spends most of his time recalling a simpler time: his childhood in the Spanish countryside spent primarily with his mother (Penélope Cruz – also doing exemplary work).

Pain and Glory is a deeply personal and, I suspect, cathartic film for Almodóvar. Yet, the movie is brimming with such keen observations on humanity and human relationships that it possibly makes Pain and Glory one of Almodóvar’s most accessible films for a mass audience. I would imagine that anyone who has ever been a child and grown up, forced to reconcile the confusing discoveries of one’s youth with the ultimate hardships of being an adult, will find something with which to identify here. Salvador’s internal struggles – coming to grips with his perceived duties as a son, his worthiness as a director, his capability as a lover – are struggles that any middle-aged person evaluating their life will recognize. Banderas illuminates Salvador’s conflicts at once in his physicality (shoulders stooped, fragile appearance), but more importantly in his face: his eyes carry the droop of defeat and the lines of age appear somehow deeper and more cavernous than they ought to be. In one beautiful moment, Banderas does a total emotional 180 with just his eyes as he encounters an old lover outside his apartment door. It is a stark and revealing moment for a character that has been so morose for so long.

Almodóvar’s script eliminates none of his trademark humor and affection for his characters, especially the women. While the word “campy” is often bandied about when discussing the films of Pedro Almodóvar, there is hardly any of his usual outrageousness and lunacy in Pain and Glory – it’s not that kind of movie. Instead, the filmmaker has made a touching and reverential film about mothers and sons, loves lost and gained, finding one’s truth and purpose, and, finally, self-redemption.